Britannia is the Latin name given by the Romans to the present Great Britain, probably taking a form native Celtic. is also sometimes used the term Old Britannia Britannia prehistoric or to indicate that stage of English history that goes from Prehistory Roman invasion of Britain (43 AD).

"Britannia" is the Greek expression " Πρεταννικαὶ Νῆσοι " used by Pytheas of Marseilles Pitea or the Gauls, who had circumnavigated the United Kingdom between 330 and 320 BC From "Pretannia", the greek historian Diodorus gave the inhabitants of this land as "Pretani.

introduced the term used by Pytheas in the classical world coincides with Ynys Prydein , the name that the ancient Celts gave to the island. " Ynys " island (rendered in Latin by "island" in greek and with "Nesos"), an addition would be contingent, the name itself, " Prydein ", is due the Indo-European root * Kwer-, engraving, which suggests a ritual tattoos and perhaps the habit of the ancient Picts and Scots to paint the body.

The peoples of these islands were called the Prettanike Πρεττανοι , or Priteni Pretani. These names derived from a Celtic name which is likely to have reached Pytheas from the Gauls, which can be used as a term for the inhabitants of the islands. Priteni is the source of the Welsh language term Prydain, Britain, which has the same source as the Goidelic Cruithne term used to refer to the early Brythonic speaking inhabitants of Ireland and the north of Scotland. These were later called Picts or Caledonians by the Romans. Commonly

it is considered that the form "Prydein" the Romans first landed on the island by Julius Caesar in 55 BC, had learned the word "Britannia" by which they designate the northernmost island of their empire. There were at least two other regions of Britain as on the Continent: a current and a current Galicia Belgium. Also for this reason but also for historical reasons-phonetic, some would come to Britain by other roots: * bher-, carry or think, or *-bhrei, cut or judge. Britain would then, according to them, "the (head) of the (value) of thought" or "(seat) of the (brave) trial. " The basic idea in this hypothesis is that "Britons" and "Galli" would be two additional names, in fact two diminutives of the same compound, namely "Brittogalli," and that the full meaning of this would be brave of thought brave or trial. This compound is actually attested as the name of a population at the mouth of the Danube along the current border between Romania and Moldova.

According to other sources, but "Britain" is the name derived from Latin, Old French and Middle English Bretayne , Breteyne . The shape French was replaced by the words Breoton , Breoten , Bryten , Bretenière (also Breoton-Lond, Bretenière-Lond).

Following the Roman conquest of AD 43, Britain was officially designated to indicate the name of the Roman province. Pre-Roman era, Britain was known as the Albion .

In written texts, however, the possible true etymology of the name Britannia, appears only in the ninth century, during the reign of Alfred the Great, in the text Historia Brittonum. This etymology takes precedence over the others because it is made a reference to the character of Brutus of Troy [1] . Brutus and Britain have a derivation quite similar in sound in different languages, if the origin of the name is Greek, which explains why the first that spoke, that the Gauls Pitea, would give this name to the island, referring to the events character.

Brutus of Troy Brutus of Troy or Brutus I of the Britons (Welsh: Bryttys), a descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas, is known in medieval legend as the founder and first king of Britain, which had reigned for twenty-three around 1100 BC. This legend appears for the first time historia Brittonum, compilation of IX century, attributed to Nennius, but is best known from the story that he made in the twelfth century Geoffredo of Monmouth in his semi-legendary Historia Regum Britanniae. However, no reason to consider that this story is historically credible. The Historia

Brittonum states that "The island of Britain takes its name from Brutus, a Roman consul, who won both Spain and Britain. Following sources such as Virgil and Livy, The History Brittonum tells how Aeneas is established in Italy after the Trojan War and how his son Ascanius founded Alba Longa has. Ascanio was married and his wife became pregnant. A magician predicted that would be born a male, which would have been the bravest and most beloved in Italy. Enraged, the soothsayer Ascanio condemned to death. His wife died in childbirth, while later their son, of course Brutus, accidentally killed his father with an arrow and was banished from Italy. Having roamed the islands of the Tyrrhenian and Gaul, where he founded Tours, Brutus arrived and settled in Britain. He reigned when the high priest Eli was the judge in the kingdom of Israel and the Ark of the Covenant was taken by the Philistines. A different version

dell'Historia Brittonum states that Brutus was the son of the son of Ascanius, ie Silvio, and traces his genealogy to Cam, the son of Noah. Another chapter provides a different but genealogy of Brutus, who here becomes the great-grandson of the Roman King Numa Pompilius, son of Ascanio, tracing its lineage to Japheth, the son of Noah. These traditions Christianized contrast with the classic Trojan which connected the royal family of Priam with the Greek gods.

Another Brutus, son of Isicione, son of Alan the first European, is traced back to Iapetus dall'Historia Brittonum. The brothers of these brutes were Franco, Alamo and Roman ancestors of some major European nations.

Geoffrey of Monmouth shows more or less the same story but with more detail. The soothsayer who predicted big things for Brutus, however, also predicted that he would have killed both parents. So it happened and he was banished from Italy. He went to Greece, where he discovered a group of Trojans who were there as slaves. He became their leader and after a series of battles, the king greek Pandraso [2] let them go. Brutus married the daughter of this king, Ignoge , and ships with supplies and took the sea route. Having had a vision that promised him a kingdom, inhabited only by a few giants, who could conquer, Brutus led his people west.

After some adventures in Africa and a meeting with the sirens, Brutus found another group of Trojans, led by warrior Corineus [3] . It was to blow up in a war with Gaul Goffario Pitto, king of Aquitaine, for he had hunted in the royal forest without permission. The nephew of Brutus, Turono, died in battle and the place of his burial was founded the city of Tours. Although they had won many battles, the Trojans were aware that the roosters were greater in number and then went to the island called Albion and Brutus, by its very name, called Britannia, where he became the first ruler. Corineus instead became king of Cornwall, who was named in his honor after his death. Attacked by Giant, the Trojans killed them. On the banks of the River Thames Brutus founded the city of Troia Nova, a name that subsequently became Trinovantum: This is London although the Romans called it with the name that most reminds Londinium.

Before his death, Brutus promulgated a code of laws for his people. Ignoge his wife had three children: Locrino, Kamber and Albanatto that, when his father died, they divided the island, respectively England, Wales and Scotland.

Figure 1 - Dover, England

Albion or Albion Albion

(Ἀλβιών in ancient greek) is the ancient name of Britain's oldest, before they reach you Brute Toria. Today it is used poetically to refer to the whole island or just England. Occasionally the term Albion is referred to Scotland, whose name in Gaelic, however, is Alba.

The term Gallo-Latin Albion (Middle Irish Albbu, protoceltico * Alb-ien-), together with other European and Mediterranean names, has two possible etymologies, both plausible albho-*, protoindoeuropeo for "white", or * alb-, protoindoeuropeo for "hill". The word from the Latin dawn is the feminine singular form of albus, meaning "white" and would refer to the white cliffs of the island.

The name Albion was introduced by Rufio Festo AVIEN, was then taken up by Pitea which would have changed the word from which the Romans would have translated the word Britain. Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia, however, uses the word "Alba" to refer to its entire British Isles.

It becomes ambiguous, the origin of the word Britannia Albion and the deadline, probably Britain takes its name from Brutus, and then was adopted as the first term if one follows the mythological story of the island and its history. If you follow the historical sources on the island may have been known first as Albion and later as Britannia. It would not be impossible, however, that during the Middle Ages and in earlier times, the island was known on both names.

primitive

Britannia Britannia was inhabited by humans for tens of thousands of years, and Homo sapiens for ten thousand years. However, no pre-Roman population had a written language and for this reason everything that is known about their culture and their way of life comes from archaeological findings. The first written mention of the Britannia and its people dates back to the greek navigator Pytheas of Marseilles (Greek colony), which explored the British coast around 325 BC However, from the ancient Neolithic Britons were involved in trade intense commercial and cultural relations were with the rest of Europe, exporting mainly tin, when the island was rich.

Located on the borders of Europe, Britain was left behind in the field of technological and cultural progress throughout prehistory. The ancient history of Britain is characterized by successive waves of settlers from the continent, bringing with them new cultures and technologies. The latest archaeological theories have questioned this theory migratory giving more emphasis, instead, for the existence of a more complex relationship between Britain and the Continent in archeology today suggests that many of the changes taking place in British society were caused adoption , by the natives of foreign customs.

The Palaeolithic Palaeolithic man went to Britain, roughly 750,000 to 10,000 BC. In this long period there were many changes both environmental (including many glacial and interglacial periods) and the human settlement in the area. The inhabitants in this period, were bands of nomadic hunter-gatherers, who chased the herds of animals throughout northern Europe. There is evidence of human presence in Britain 400,000 years ago. At that time, the island was connected to continental Europe by a land bridge. Stone axes, found in Somerset in the seventies, they suggest the existence of Palaeolithic settlements of Homo erectus, an ancestor of modern man. From 230,000 BC Neanderthal man (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) lived in what is now Britain and ousted the Homo erectus. Evidence of the production of flint tools by Neanderthals have been found in Kent, southern England. Modern man (Homo sapiens sapiens) appeared for the first time in Britain around 30,000 BC The first human inhabitants of Britain were made in the tribe of hunter-gatherers. During most of this period most of Britain remained uninhabited due to the glaciation.

Bones and flint tools found on the coasts near Happisburgh in Norfolk, and Pakefield, Suffolk show that Homo erectus was already present in Britain around 700,000 years ago. At that time, the south and east were connected to continental Europe by a wide land bridge, allowing people to move freely. The current English Channel was a large river that was heading west and was fed by the tributaries, later became the current Thames and the Seine. This reconstruction has provided the first clues about the route used by the inhabitants of Eurasia to arrive in Britain and it would be a lost river called Bytham.

sites as Boxgrove in Sussex attest to the subsequent arrival of Homo heidelbergensis, around 500,000 years ago. The human species produced Acheulean flint tools and hunted large mammals of the time. They used to drive the elephants, rhinos and hippos at the top of cliffs or into bogs to more easily kill them. It is likely that the rigors of the next ice age] made a total of migrating men from Britain and the region does not seem to have been busier when the ice broke up in the interglacial period known as the Hoxne. This warmer period can be placed between 420,000 and 360,000 years ago and saw develop processing tools silica Clactonian in places such as Barnfield Pit (Kent). No word yet on whether there was a relationship, and if so what kind, between industries and the Acheulean Clactonian.

Figure 2 - The Sanctuary on Overton Hill, 5 miles west of Marlborough, in Wiltshire.

During the new period of intense cold, which lasted until about 240,000 years ago, there was the introduction of the so-called flint tools of Levallois technology, perhaps by men from Africa. But discoveries made in Swanscombe and Botany Pit support the hypothesis that Levallois technology came from Europe and Africa. This advanced technology yields more efficient hunting and therefore the easiest place Britannia where to stay during the Ice Age. However, there is little evidence of human occupation during the next interglacial period that Ipswich (about 120,000 years ago). The melting of ice cut out for the first time during this period Britain from the continent. And that could explain the low level of human activity. In general, seems to have been a gradual decrease in population between the interglacial Hoxnian el 'Ipswichian and the absence of archaeological traces of human beings suggests that it would have been the result of a gradual depopulation.

Figure 3 - A memorial on Round Loaf.

Around 6500 BC, the end Ice Age produced a rise in sea level, which cut off Britain from continental Europe and made it an island.

Around 4500 BC began to emerge the first agricultural settlements, when immigrants from Europe arrived, bringing with them knowledge of agriculture. In 3500 BC the agricultural settlements existed in much of Britain. We have found clay pots dating back to 4100 BC

Around 2500 BC a new culture arrived in Britain, carried by a group of people known as the Beaker culture. Deemed to be originating in the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal), these people took to Britain's ability to manufacture weapons and metal tools. Initially using copper, but from 2150 BC, smiths discovered how to produce bronze (which is much harder than copper) by mixing copper and tin. Thanks to them the Bronze Age arrived in Britain. Over the next thousand years, bronze gradually replaced stone as the main material for making tools and weapons.

Figure 4 - The complex of Stonehenge, possibly built around 2500-2000 BC

Britannia had large reserves of tin in the areas of Cornwall and Devon, in the South of England, and then began the extraction the pond. Around 1600 BC, the south-west of Britain experienced a business boom, and the British tin was exported across Europe.

The people of the Beaker Culture was also skillful in the production of gold ornaments, and many examples of these products have been found in the tombs of the wealthy.

The Beaker people buried their dead in mounds of stone, often with a beaker alongside the body (Beaker in English means "cup"). They were also largely responsible for the construction of many famous prehistoric sites such as Stonehenge (although an earlier circle of wood in that place existed), and several stone circles.

From about 1500 BC, the power of the Beaker people began to decline.

There is debate among archaeologists about whether the Beaker people were a race that migrated to Britain en masse from the continent. Or when the Beaker culture, which was common throughout Europe, was widespread in Britain through trade and cultural links. Modern thought is inclined to the latter.

Around 750 BC iron working techniques reached Britain from southern Europe by bringing the Iron Age. The iron was stronger and more abundant the Bronze Age, and revolutionized many aspects of life. The most important was agriculture. The iron plow with the tip could tilling the soil faster than the previous wood or bronze, and iron axes could clear the forests more efficiently.

The Celts around 900 BC a new wave of settlers arrived in Britain. These are known as the Celts, and 500 BC had colonized most of Britain. The Celts were highly skilled craftsmen and produced jewelry with intricate patterns and bronze weapons and iron.

The Celts lived in highly organized tribal groups, typically governed by a chieftain. Their groups were organized in a "high class" of warriors (which typically is made of the long growing mustache) and a "lower class" of slaves and workers. Normally, the Celts lived in simple huts.

Celtic warriors were known to be fierce and fearless warrior women and pipelines were not unknown. The most famous of these was Boudicca.

The Celts practiced paganism, under the guidance of the Druids (priests). The class of Druids was almost as powerful as the warriors in Celtic tribes. Celtic culture had no written language, and laws and rituals were passed down orally. When the Celts

increased number of fights broke out between rival tribes. This led to the construction of fortifications. Although the first had been built already in 1500 BC the fortifications reached their peak in the Celtic period.

These fortifications consisted of an area of \u200b\u200bhigh ground surrounded by a deep trench, the earth piled up in banks. The area was also surrounded by a palisade. This configuration was easy to defend from the attacks, these buildings were originally designed as places of temporary refuge. However, with the passage of time, the fortifications became ever larger and housed permanent settlements and centers of commerce.

Many of these fortifications were built in the west and south-west, even if they are found in samples from northern Scotland. The

last centuries before the Roman invasion saw an influx of refugees from Gaul (modern France and Belgium), known as the Belgians, who were displaced by the expanding Roman Empire.

From about 175 BC, settled in the areas of Kent, Hertfordshire and Essex, and brought with them a skill in pottery, much more advanced than that used previously. The Belgians were Romanized and were partially responsible for the creation of the first settlements large enough to be called cities.

Even if there was anything that would resemble the political unity among the different tribes living in Britain, the evidence suggests that life became more stable, less warlike.

The last centuries before the Roman invasion, they saw a growing sophistication of British life. Bars of iron began to be used as money since 100 BC, and the domestic trade with continental Europe flourished, thanks largely to the vast mineral reserves of Britain.

With the northward expansion of the Roman Empire, was probably due to the fact that many refugees from areas occupied by Roma moved there, or because of its mineral reserves, that Rome began to be interested in Britain.

The Britons The Britons were a Celtic tribe in ancient times allocated British Isles (Great Britain and Ireland). Arrived in the region from the eighth century BC, the Celts of Britain were broken up into numerous tribes, thus facilitating the conquest of their territory before the Romans (first century AD), and Anglo-Saxon (V century). The Britons were subdued polychaete and culturally to the new rulers, but their Celtic civilization was never completely eradicated, by helping to form (together with the contributions of Latin Christians and Germany), the modern populations of Great Britain and Ireland, so much so that British-born are the only Celtic language survived until today.

The main source is Caesar on the Britons, who in his De bello Gallico said the two expeditions undertaken by him in Britain in the mid first century BC. Other news we owe to Imilcone Carthaginian navigator, who in the fifth century BC had taken a trip to these lands, and the greek geographer Pytheas (IV century BC).

From the eighth to sixth centuries BC, groups of Celts invaded the British Isles several times, overlapping the previous inhabitants. These groups came through the English Channel from continental coasts of Europe, the Celts had just arrived after starting their expansion from the cradle of their people (the area of \u200b\u200bCulture The Tène) and down the Rhine during Starting South of England from today, they expanded rapidly in Great Britain and Ireland even if the people of Scotland in the current pre-Indo-European Pictish retained their individuality.

Like all Celts, Britons never reached a political unit, in some rare moments when they entered into provisional leagues military, facing a common enemy. Gaius Julius Caesar in 55 BC who arrived with his fleet in Britain, the distinguished people in coastal and native, who had emigrated in the second century BC in Belgic Gaul and had created powerful states. Among the people most important to remember the Cantiaci, who lived in Kent today (which takes its name from them), the Dumnonii, in the Cornwall, and, further north, the Iceni.

Caesar attests to the close links, not only cultural but also economic and political, between the Britons and Gauls: Divitiacus domains, for example, extended on both sides of the Channel and the island escaped refugees from Gaul, who in turn obtained, if necessary, military aid from Britain.

in the war for the conquest of Gaul, Julius Caesar led two quick forays into Britain in 55 and 54 BC. Caesar's attention during his De bello Gallico [5] The first shipment (late summer 55), which did not achieve great results, it was more of a reconnaissance expedition. The troops landed by sea on the coast of today's Kent. The second invasion, that of 54, was more successful: Caesar imposed on the throne the king Mandubracio friend and forced his opponent into submission, Cassivellaunus, even if its territory was not subdued.

Britons remained independent until 43 AD when the Roman Emperor Claudius launched the invasion of the island, and entrusted to Aulus Plauzio. The defeated general Caratacus Catuvellauni king and leader of the anti-Roman resistance, and gave it to the domain beginning Latin. As a result, new expeditions were led by Publius Scapula Ostorio (47-51) and Suetonius Paulinus (60-61) (who fought and won the indomitable queen of the Iceni, Boudicca) and Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who conquered the lands of Briganti and defeated the tribes of modern Scotland. The Romans occupied the area of \u200b\u200bthe current England and Wales, erecting a north fortified limes: Hadrian's Wall (122), then moved further north (Vallo di Antonino, 142). Apart from the limes (the current Scotland and Ireland) were both British tribes, and the Picts. During Roman rule, among the Britons the influence of Latin language and culture only penetrated deeply into the upper classes, while the people continue to preserve the Celtic tradition: the cessation of Roman rule in Britain (late fourth or early fifth century ) ethnic identity and language of the Celts was still alive and survived for a long time after the Germanic invasions. The Roman domination, and in particular the grant of Roman citizenship to large sections of the local population, generating a level of cultural identification and ethnic mix: that of the Romano-Britons, then absorbed by the dominant element of Celtic or Anglo-Saxon invasion induced by the flight to the Romanized regions of the continent Europe.

Roman rule in Britain ended in the early fifth century, when the legions left the island (about 410), leaving her at the mercy of invading Saxons, Jutes and Angles. Thus began the Anglo-Saxon period, which would end in 1066 with the Norman conquest. With the arrival of the Anglo-Saxon invaders, part of the British Celts migrated into the region dell'Armorica (now Britain). The English Middle Ages had begun.

The merger of the three elements (Celtic, Germanic and Latin) would be formed in this period, the modern populations of Great Britain and Ireland (although the second of the British Isles had suffered only indirect influence Latin element, However, this was particularly crucial in the cultural field, through the process of Christianization). The only modern peoples direct heirs of the ancient Celts are those of the British Isles, which would have preserved the unbroken tradition of language giving rise to the Insular Celtic languages, in both houses Goidelic and Brythonic.

Britain suffered, since the fourth century, a process of re-celtizzazione by teams from nearby Ireland, never entered the dominions of Rome. Since the mission of St. Patrick in Ireland (432), the island enjoyed a flourishing religious, through the missionary outreach, protection of the Celtic heritage, although now supplemented with new elements of Christian origin. A few years back the earliest evidence of Insular Celtic languages.

The expansive phase of the Celts Irish characterized the last centuries of the millennium and interested mainly in Scotland and the Isle of Man This activity was, however, only cultural and religious from the political point of view, in fact, Ireland was invaded and controlled by the Vikings in the eighth to ninth century Germanic.

Despite the lively culture, the heirs of the Britons were - except in rare moments, like after the Battle of Carham (won in 1018 by King Malcolm II of Scotland) - always subject to new rulers, all of the Germanic languages: the Vikings and the first Anglo-Saxons then. The Celtic identity underwent a process of retreat, as witnessed by the progressive reduction of the area occupied by native speakers of different varieties of Insular Celtic languages.

The second millennium has seen a steady regression of the surviving Celtic elements, subjected to a continuous process of both linguistic Anglicization, both political and cultural. From the melting of the Celtic and Germanic (Viking and Anglo-Saxon) are derived, ethnically and culturally modern populations of Great Britain and Ireland: not more so - and since the Middle Ages - Celtic people in strict sense, but modern heirs of the ancient Britons, variously hybridized - like any other European people - with several successive injections. The Britons

mined and traded tin, grew wheat and raised cattle. In particular, the pond was commericato of the Britons, by the Gauls, in the whole Mediterranean basin.

are almost no surviving evidence of the British language, spoken by the ancient Britons. Although the language differs Continental Celtic languages \u200b\u200band Celtic languages \u200b\u200bisland, this division is not despite the name, geographical location, but chronological: the former being attested in ancient times (and there is no evidence of Celtic languages \u200b\u200bspoken on the British Isles prior to the fourth century AD), the latter are those certified since the Middle Ages (and present its and exclusively on the British Isles. However, many sections of the first entries in the alphabet Ogami found in Ireland (as defined in Irish archaic or proto-Irish) provide linguistic traits similar to those of the Continental Celtic languages, such as the absence of lenition.

Britannia Medieval: the evolution of V and VI of the province cesarean sec

The ancient Roman province of Britannia crossed in the fifth and sixth centuries a period of profound transformation, including the cessation of Roman rule and the emergence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

The term "post-Roman Britain" (Sub-Roman Britain in English) is a designation initially used in archeology to indicate the material culture of the region in late antiquity and in this period. The use of the term was linked to the idea of \u200b\u200bdecay in the quality of production, particularly of ceramics with respect to those present during the Roman Empire. This historical reconstruction was subsequently passed and the deadline is then passed to indicate the historical period.

The conventional dates for the period are set for its beginning to the end of Roman rule, with the departure of the last garrison in 407, and its arrival order of St. Augustine of Canterbury in England in 597. The post-Roman culture, however, also continued in later periods especially nel'lInghilterra West and Wales.

The term refers in particular to the territory that had been included in the Roman province of Britannia, to the so-called "Forth-Clyde line, north of which were the regions controlled by the Picts.

In this era, the culture was represented by a mixture of elements of Roman and Celtic elements, but the element of Saxony, already occasionally From the beginning, gradually assumed control of territory and a dominant cultural position with the establishment of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Written sources refer to this period are particularly scarce, although the period is treated in subsequent reports with numerous inventions, more or less legendary.

Among the contemporary local sources need to be addressed are the Confessio (or "Statement") of St. Patrick and the De Excidio Britanniae (or "the ruin of Britain") of St. Gildas. The first is most useful with regard to the condition of Christianity at the time and reveals some aspects of the life of the period, while the latter work was intended to warn the rulers through contemporary examples: the historical materials are therefore selected in view of the intended purpose, are not mentioned dates and some details are incorrect. In some cases the evidence on the kingdoms at the time existing and the development of relations between the Britons and the Anglo-Saxons are the only ones that have reached us.

There are also other contemporary sources which mention the Britannia, but were drawn in continental Europe. Among these is the famous rescript of the Roman Emperor Honorius of the West, quoted by Zosimus, a Byzantine historian of the sixth century in his history NEA. The rescript was addressed to civitates (city) of Britain, asking them to make their own for his defense. However, since Zosimus speaks of dealing with events in southern Italy was also supposed that it could actually refer to the Italian region of Bruttium, rather than Britain.

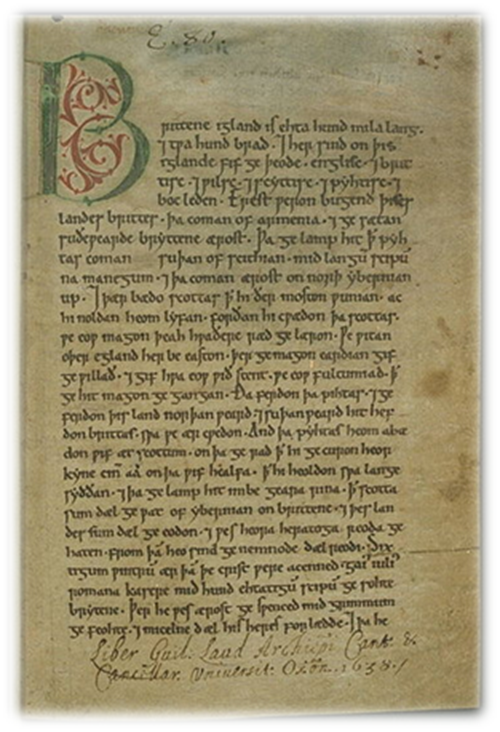

The Gallic Chronicle is confined to inaccurately report that Britain, abandoned by the Romans would have ended up directly in the hands of the Saxons, and also provides information on travel to St Germain d'Auxerre in the region. The references to Britain who are in the works of the Byzantine historian Procopius are considered to be of dubious reliability. Among the later sources who have treated of this period, it must be mentioned the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum of the Venerable Bede (early eighth century), based on the aforementioned work of Saint Gildas: the work provides the dates of events, but the narration is done by an anti-British point of view. The Historia Brittonum, traditionally attributed to Nennius monaco Welsh, from the early ninth century, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a compilation annals compiled at the end of the century and based on West Saxon sources, and Annales Cambriae or Annals of Wales " ; of the late tenth century, mixing history and myth and require cautious interpretation.

Other historical writings subsequent to the Norman Conquest are based sull'Historia Regum Britanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth, which, although presented as a historical work is now recognized as a great guide with only a few historical references. The historical references contained in the lives of the saints are, finally, for the most unreliable and the result of later compilations.

The number of objects belonging to this period was found during excavations seems more limited than the earlier Roman period, the apparent trend towards greater use of perishable materials like wood or leather. The excavated sites have mostly returned buckles, ceramic vases and weapons.

The study of funeral rites, burial or cremation, funeral and made it possible to acquire data on the social structure and cultural identity of the people, highlighting substantial continuity with the previous Roman period, the presence of influences from Celtic and maintain business contacts with the Mediterranean world

In some cases, as in the necropolis of Wasperton in Warwickshire, has witnessed the coexistence of Britons and Saxons and other sites are evidenced the mutual influences between the two cultures.

settlements suspects were mostly made in fortified hill towns (called "hill forts" or, in English, hillforts), city and monasteries. A Tintagel excavations in the '30s by Ralegh Radford have unearthed a rectangular structures dated to the fifth-sixth century, originally interpreted as a monastery and later as a fortified mall, where was found a considerable amount of pottery from the Mediterranean.

Other excavations were conducted by Leslie Alcock in the 60s in Dinas Powys, with evidence of metallurgical production, and in the 90s at Cadbury castle, an Iron Age fort reoccupied between 470 and 580.

Other sites that have shown traces of occupation in post-Roman period are the city of Wroxeter (Viroconium) and the Roman forts of Banna on Hadrian's Wall (now Birdoswald) and those of the defensive line Litus saxonicum.

Investigations in the field of archeology environmental and survival have also documented changes in agricultural practices.

Figure 5 - The first page of the Peterborough Chronicle (Conac Anglo-Saxon)

the beginning of the fifth century we know that the Roman province of Britannia was still part of the Western Roman Empire, under Emperor Honorius. Since the end of the previous century had experienced an economic slowdown, with the decrease of new coins and related difficulties in the payment of money to the army. In 407 troops still remaining in the British garrison, already decreased in the period prior to the transfer intended to meet the military barbarian invasions in continental Europe, elected to the imperial throne usurper Constantine III. They moved with all the forces still available on the island beyond the Channel, to face against the army sent to him by Honorius, from which he was defeated and killed in 411. After the departure of the last garrisons were apparently the inhabitants of the territory to be protected from incursions Saxon and the rescript of Honorius quoted by Zosimus, if it refers to Britain, confirms this fact.

gradually take the place of Roman officials and institutions of local feudal rulers. Fighting between different groups were interpreted as conflicts between favoring and opposing independence from the Roman Empire, or between followers of the Roman church and Pelagianism, or even as social conflicts between peasants and landowners linked urban elite. Daily life still had to continue almost unchanged in the countryside and urban decline, as seems to be held in Britain in the report of the visit of Saint Germain d'Auxerre.

According to the report of St. Gildas, Vortigen, the Venerable Bede called "king of the Britons" and date to around 446, he decided to bring in mercenaries to defend against Saxon incusioni foederati as barbarians, according to the Roman , room "in the eastern part of the island." Later, the Saxons increased in number from other arrivals, they would have rebelled and would be given the sack. They would then fight the British and Roman Ambrosio Aureliano, who may have been the historical basis for the figure of King Arthur and who is said by some sources to the victory of Mount Badon, around the year 500.

Advanced Saxon Britons was arrested and remained in possession of England Wales and west of the line which connects York and Bournemouth, while the Saxons controlled the Northumberland, East Anglia and the south-east of ' England. St. Gildas mentions other British rulers: Constantine Dumnonia, Aurelio Canino, Vortipor of Demet, Cuneglasso and Maglocuno.

by the Britons to the Anglo-Saxons

Relying mainly on written sources, the historical reconstruction envisioned that a traditional Anglo-Saxon mass immigration during the post Roman period had resulted in the disappearance of the Britons. The event was also thought of as violent and rapid.

The linguistic data seemed to support this interpretation. The current topography of England, with the exception of Cornwall shows, in fact, traces of limited terms of Celtic origin, though less rare as you move from east to west. They are also very scarce in the words of the ancient Celtic language that has passed English.

The spoken Latin and Celtic, the latter long remained in use as a written language, although it ignores the spread as a spoken language, seem to be only gradually been replaced by spoken Germanic. There are also some names of Latin origin, suggesting a continuity of settlement. In some cases there are also names referring to the ancient Germanic gods.

Since the '90s, the interpretation of the data was last changed: it now considers in general unlikely that a large wave of immigration had swept the Anglo-Saxon Britons. The Saxons are rather considered as the ruling elite, while the British were slowly assimillati their culture. The recent genetic tests appear to have suggested that the contribution be identified as the genetic profile of the current Anglo-Saxon England is largely minority. The code of laws attributed to King Ethelbert of Kent, in the early seventh century, and the King Ine of Wessex at the end of that century or early next, refer to an inferior legal status attributed to the general public, that the collection later identified as that is clearly of British origin. Scholars and clergy from Britain, however, had to play an important role in the formation of Anglo-Saxon culture, previously predominantly oral.

Some Britons had already moved from the fourth century over the English Channel, dell'Armorica in the region, which was later known as Britain and maintained throughout the period, close liaison with Britain. Other Britons came up in Galicia, where the bishop of "Briton", mentioned in a document of 572, had the name Celtic Mailoc and where the emigrants left the Celtic Christianity only with the council of Toledo in 633.

The endemic tension and violent struggles of this period, which allude to all the written sources, and the decline in output seen in the archaeological record, however, had to lead to a decline in population. The data provided by dendrochronology also seem to confirm that there was a period of colder climate and humid about 540, which must have contributed to the decline in agricultural production. There was added in 544 or 545 to arrive in Great Britain and the plague of Justinian.

Figure 6 - The kingdoms of the British Isles around the year 500.

Kingdoms of the fifth and sixth centuries

Kingdoms of Britain

- Bryneich, then Anglo kingdom of Bernicia (northern England)

- Brycheiniog (south Wales)

- Caer Badden (Bath)

- Caer Ceri (Cirencester)

- Caer Gloui (Gloucester)

- Dumnonia (Cornwall and Devon)

- Dyfed, or Demet (South West Wales)

- Ebrauc (York), then the kingdom of Deira Anglo

- Elmet (West Yorkshire)

- Glywyssing (South Wales)

- Gododdin (northeast England)

- Gwent (South Wales)

- Gwynedd (North Wales)

- Powys (Mid Wales)

- Rheged (north-west England)

- Strathclyde (Scotland South)

Brycheiniog, Ebrauc, Elmet, Gododdin, Rheged and Strathclyde, formed what was known in later tradition Ogledd as Yr Hen (Welsh for "Old North"), in the region between Hadrian's Wall and the Anthony. Repairs totaled fifth and sixth centuries along the Hadrian's Wall (at Whithorn in south-west Scotland).

The British kingdoms that were formed in the western part of England, had originally come from modification of the structures of Roman provincial jurisdiction, but also had clear links with those that were formed during the same period in Ireland, which had never been subject to Roman rule. In some Roman cities, like Caerwent and Wroxeter, is demonstrated continuity of employment in this period, probably related to ecclesiastical structures.

addition to Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira, which correspond to the British Empire with a different name after their conquest by the Angles and formed as a result of the united kingdom of Northumbria, the largest Anglo-Saxon kingdoms present in post-Roman period, including as a result of Anglo-Saxon nell'eptarchia were:

- East Anglia (Suffolk and Norfolk)

- Kent (county of the same name)

- Mercia (Midlands)

- Sussex (historical county of the same name)

- Wessex (southern England and south West)

- Essex (southeast England)

- Northumbria

- states of medieval Britain

- kingdoms of the Jutes:

- Kent

- Meonware

Regni degli Angli:

- Anglia orientale

- Hwicce

- Iclinga

- Bernicia

- Deira

- Lindsey

- Regno del Lindsey

- Magonsete

- Pecset

- Mercia

- Northumbria

Regni dei Sassoni:

- Ciltern Saetan

- Middlesex

- Surrey

- Sussex

- Wessex

- Essex

Stati britanni meridionali

- Brycheiniog (Brecknockshire)

- Buellt (Builth)

- Caer Baddan (Bath)

- Caer Celemion

- Caer Ceri (Cirencester)

- Caer Caer Colun

- Gwinntguic

- Caer Gloui (Gloucester)

- Caer Lundein (London)

- Caer Went

- Calchvynydd

- legendary Camelot =

- Cateuchlanium

- Ceredigion

- Cerniw

- Deheubarth

- Demez

- Devon

- Dogfeiling

- Dunoding

- Dyfed

- Vale of Clwyd

- Dumnonia

- Edeyrnion

- Elwel

- Ergyng

- Glastenning

- Glywysing

- Gorfynedd

- Gwerthrynion

-

- Gwent Gwynedd

- Gwynllwg

- Gwyr (Gower Peninsula)

- Gwent

- Ynys Vectis (Isle of Wight)

- Llyn

- Lyonesse (Scilly Isles)

- Meirionydd (Merionethshire)

- Mon

- Morgannwg (Glamorganshire)

- Pengwern

- Penychen

- Powys

- Rhegin

- Rhos

- Rhufoniog

- Seisyllwg (Cardiganshire/Ceredigion)

- Ynys Vectis (Wight)

- Ystrad Tywi

Stati britanni del nord, gaelici, pitti e caledoni

- Alba

- Alt Clut

- Angus

- Argyll

- Attecotti

- Caer Guendoleu

- Cat

- Caithness

- Ce

- Cumbria

- Dál Riata

- Dunoting

- Ebrauc

- Elmet

- Fib

- Fortriu

- Gododdin

- Meicen

- Moray

- Orcadi

- Pennines

- Pictavia

- Rheged

- Strathclyde

- of Man United States

Danish, Norwegian and Dubliners

- Cumbria

- -Gaelle Gaedhill (Galloway)

- United Man

- Earldom of Orkney

- Danelaw

- Yorkshire

heptarchy (from the greek ἑπτά + ἀρχή seven sovereignty) Anglo-Saxon is the name given by historians of that period in the history of England after the Anglo-Saxon migration of the southern part of the island (which they took the name "Angleland", from which England). This period comes conventionally until the Vikings began their raids on the island, establishing the Danelaw and reign in York and the Isle of Man So from about 500 to 850 or so.

heptarchy The term refers to the existence of seven kingdoms, which later merged to form the Kingdom of England, in the first half of the tenth century. The term was coined in the twelfth century and became common use since the sixteenth.

More recent research has however, it is shown that some of these kingdoms (Essex and Sussex) had the same status as other, both on the island that there were also other smaller kingdoms that had a not insignificant role.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century the term heptarchy was considered unsatisfactory to describe the situation and many historians have stopped using it.

Notes

[1] Brutus of Troy or Brutus I of the Britons (Welsh: Bryttys), a descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas, is known as the medieval legends founder and first king of Britain, which had reigned for twenty-three around 1100 BC. This legend appears for the first time Brittonum historia, compilation of IX century, attributed to Nennius, but is best known from the story that he made in the twelfth century Geoffredo of Monmouth in his semi-legendary Historia Regum Britanniae. However, no reason to consider that this story is historically credible.

[2] Pandraso : mythological king of Greece, the root of the name is derived from Pan and Pan, the God of the form greek goats. derives from the greek paein , graze. But literally means pan all because according to Greek mythology Pan was the spirit of all natural creatures, and this meaning ties him to the forest, the abyss, the deep. Its name derives from the word panic, the god is angry with those who disturb him, and began shouting terrifying disorder causing fear.

Some stories say that the same Pan was seen fleeing in fear of his doing. It is a powerful and savage god, is depicted on the outside with goat legs and horns, with hairy legs and hooves, while the torso is human, the bearded face and the expression terrible. He wanders through the woods being chased by the nymphs, playing and dancing. It is very agile, quick in the race and unbeatable in the jump. It is mostly referred to as Lord god of fields and woods in the hour of midday, protecting the flocks and herds, the tops of the mountains are sacred. Pan did not live on Olympus: Earth's lover was a god of woods, meadows and mountains. Pan was a god perennially cheerful, revered but also feared. Its name derives from the word panic. So tied to nature and the visceral pleasures of the flesh, Pan is the only god with a myth about his death. Participated in the Pan Titanomachia, having a key role in the victory of Zeus on Typhoon. Typhon was a monster that was born of Gaea and Tartarus, who wanted to avenge the death of her children, Giants. The same Giants come by another way to be part of what is the Celtic mythology of Britain as regards the construction of the megaliths like Stonehenge. A Pan is dedicated to the zodiac sign Capricorn, a gift from Zeus for her allegiance. Pan is a god with a strong sexual nature, he loved both women and men, and if he could not possess the object of his passion he indulged in lewd practices and onanistic. Many mythological stories tell us of this god and his relationship with the nymphs who sought to possess. So much so that they were saved only transformed, though not often disdained the attentions of the god. As earth-bound god and fertility of the fields is related to the Moon, and the forces of the great Mother. Among the myths that accompany it sees a seducer of Selene, which is presented by hiding under a pile white goat hair. The Goddess did not recognize him and agreed to the union. But most likely this myth is confused with the sacred union of the great mother Celtic Cernunnos, also saw the appearance of the two male gods. Pan was a god endless but also generous and good-natured, always willing to help those who ask for his help. The sexual aspects of this deity, especially the legends about the god and the nymphs have a thread of connection with what were known as the sacred marriage of ancient Britain, the Celtic tradition, the god and the goddess personified by two strangers (often started) that carnal union confirmed the link between man and the earth, and with the gods from which they came and to which he would return. As with Cernunnos, there is a current of thought that says that this pagan god was later taken over by the Christian Church to use its image as the iconography of the devil.

The ending "Just-drasus" may be a variant of the greek word "δράκος" and Latin "draco " so the full name could not be wrongly translated as Pan-- Draco, and therefore could be combination with the origin of the name or Pandragon Pendragon, the name used to designate Uther, the father of King Arthur. The daughter is Pandraso Ignoge. The latter can have no reference to the character of the Duchess of Cornwall Igraine, since in this case would be in direct contradiction to the Celtic tradition has it that the bride had been Igraine (stolen) or of Uther Pendragon and Uther denies any kinship between the two, although they are the same Celtic origin, according to the texts of Geoffrey of Monmouth.

[3] Corineus : Corineus or Corin was in British mythology a prodigious warrior, able to face the Giants, and the eponymous founder of Cornwall. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, he led the descendants of Troy with Antenor fled from the siege of Troy and took refuge on the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea. After Brutus of Troy, son of the Trojan prince Aeneas, was exiled from Italy and freed the prisoners Troaini in Greece Corineus and met with his people, and joined them on their journey. Once in Gaul, Corineus provoked a war with the King of Aquitaine, Goffrarius Pictus, hunting in his forest without permission, and massacred thousands of enemies with his battle-ax. After defeating the king of Aquitaine, the Trojans crossed the sea to the island of Albion, which Brutus renamed Britannia in his honor. Corineus settled in Cornwall, which was then inhabited by giants. The great battle between the people of Cornieo and the giants led by their chief Gogmagog was hard but eventually won and left the Trojans alive for only a direct confrontation with Gogmagog Corineus. The fight took place according to legend, near Plymouth and won Corineus the giant by throwing it on a rock. In this way Corineus was counted as the first Duke of Cornwall and when Brutus died, the rest of Britain was divided between the sons of Corineus.

Bibliography main

& # 160;

Bibliography secondary

- Brittonum Historia trans. JA Giles, Six Old Chronicles Inglese, London: Henry G. Bohn, 1848. Full text from Fordham University.

- John Morris (ed), Nennius: Arthurian Period Sources Vol 8, Phillimore, 1980

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historia Regum Britanniae, trans. Lewis Thorpe, Penguin, 1966

- The British History of Geoffrey of Monmouth, trans. Aaron Thompson, revised and corrected by JA Giles, 1842

- Rodney Castledon: The Stonehenge People - An exploration of life in Neolithic Britain 4700-2000 BC. Routledge, London 1987. ISBN 0-415-04065-5

- Nicola Barber, Andy Langley, British history encyclopedia: from early man to present day. Parragon, Bath 1999. ISBN 0-7525-3222-7

- Hector Munro Chadwick, Cruithentuath in Early Scotland: the Picts, the Scots & the Welsh of southern Scotland, (in English) CUP Archive, 1949. 171

0 comments:

Post a Comment